CHAPTER 11

HORIZONTAL AND VERTICAL CURVES

As you know from your study of chapter 3, the

center line of a road consists of series of straight lines

interconnected by curves that are used to change

the alignment, direction, or slope of the road. Those

curves that change the alignment or direction are

known as horizontal curves, and those that change

the slope are vertical curves.

As an EA you may have to assist in the design of

these curves. Generally, however, your main concern

is to compute for the missing curve elements and parts

as problems occur in the field in the actual curve

layout. You will find that a thorough knowledge of the

properties and behavior of horizontal and vertical

curves as used in highway work will eliminate delays

and unnecessary labor. Careful study of this chapter

will alert you to common problems in horizontal and

vertical curve layouts. To enhance your knowledge

and proficiency, however, you should supplement

your study of this chapter by reading other books

containing this subject matter. You can usually find

books such as Construction Surveying, FM 5-233,

and Surveying Theory and Practice, by Davis, Foote,

Anderson, and Mikhail, in the technical library of a

public works or battalion engineering division.

HORIZONTAL CURVES

When a highway changes horizontal direction,

making the point where it changes direction a point of

intersection between two straight lines is not feasible.

The change in direction would be too abrupt for the

safety of modem, high-speed vehicles. It is therefore

necessary to interpose a curve between the straight

lines. The straight lines of a road are called tangents

because the lines are tangent to the curves used to

change direction.

In practically all modem highways, the curves are

circular curves; that is, curves that form circular arcs.

The smaller the radius of a circular curve, the sharper

the curve. For modern, high-speed highways, the

curves must be flat, rather than sharp. That means

they must be large-radius curves.

In highway work, the curves needed for the loca-

tion or improvement of small secondary roads may

be worked out in the field. Usually, however, the

11-1

horizontal curves are computed after the route has

been selected, the field surveys have been done, and

the survey base line and necessary topographic fea-

tures have been plotted. In urban work, the curves of

streets are designed as an integral part of the prelimi-

nary and final layouts, which are usually done on a

topographic map. In highway work, the road itself is

the end result and the purpose of the design. But in

urban work, the streets and their curves are of second-

ary importance; the best use of the building sites is of

primary importance.

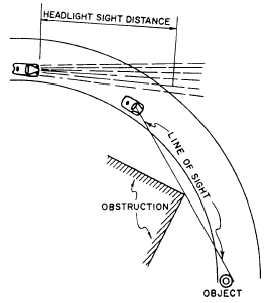

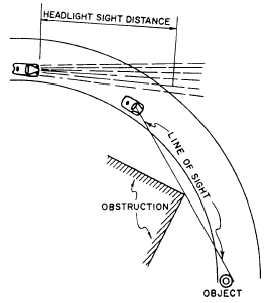

The principal consideration in the design of a

curve is the selection of the length of the radius or the

degree of curvature (explained later). This selection is

based on such considerations as the design speed of

the highway and the sight distance as limited by head-

lights or obstructions (fig. 11-1). Some typical radii

you may encounter are 12,000 feet or longer on an

interstate highway, 1,000 feet on a major thorough-

fare in a city, 500 feet on an industrial access road, and

150 feet on a minor residential street.

Figure 11-1.—Lines of sight.