drainage system; however, there are other features,

such as drainage ditches. Both storm sewers and

ditches carry surface runoff. The only real difference

between a drainage ditch and a storm sewer is the fact

that the ditch lies on the surface and the storm sewer

lies below the surface.

Similarly, there is no essential difference in

mechanical principle between an artificial and a

natural drainage system. Like a natural channel, an

artificial channel must slope downward and must

become progressively larger as it proceeds along its

course, picking up more runoff as it goes. Like a

natural system, an artificial system must reach a

disposal point—usually a stream whose ultimate

destination is the sea or a standing inland body of

water. At the terminal point of the system where the

accumulated runoff discharges into the disposal point,

the runoff itself is technically known as discharge.

The discharge point in the system is called the outfall.

Ditches.— A surface drainage system consists

principally of ditches that form the drainage channels.

A ditch may consist simply of a depression formed in

the natural soil, or it may be a paved ditch. Where a

ditch must pass under a structure (such as a highway

embankment, for example), an opening called a

culvert is constructed. A pipe culvert has a circular

opening; a box culvert has a rectangular opening.

Walls constructed at the ends of a culvert are called

end walls. An end wall, running perpendicular to the

line through the culvert, may have extensions called

wings (or wing walls), running at an oblique angle to

the line through the culvert.

Storm Sewers. —An underground drainage

system (that is, a storm sewer) consists, broadly

speaking, of a buried pipeline called the trunk or

main, and a series of storm water inlets, which admit

surface runoff into the pipeline. An inlet consists of a

surface opening that admits the surface water runoff

and an inner chamber called a box (sometimes called

a catch basin). A box is usually rectangular but may

be cylindrical. An inlet with a surface opening in the

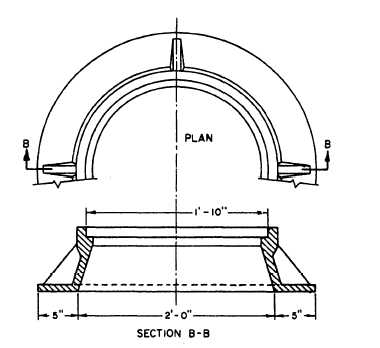

side of a curb is called a curb inlet. A working drawing

of a curb inlet is shown in figure 10-1. An inlet with a

horizontal surface opening covered by a grating is

called a grate (sometimes a drop) inlet. A general

term applied in some areas to an inlet that is neither a

curb nor a grate inlet is yard inlet.

Appurtenances. —Technically speaking, the

term storm sewer applies to the pipeline; the inlets are

called appurtenances. There are other appurtenances,

the most common of which are manholes and

junction boxes. A manhole is a box that is installed,

of necessity, at a point where the trunk changes direc-

tion, gradient, or both. The term manhole originally

related to the access opening at one of these points;

however, a curb inlet and a junction box nearly always

have a similar access opening for cleaning, inspection,

and maintenance purposes. One of these openings is

often called a manhole, regardless of where it is

located. However, strictly speaking, the access

opening on a curb inlet should be called a curb-inlet

opening; and on a junction box, a junction-box

opening. Distances between manholes are normally

300 feet, but this distance may be extended to a

maximum of 500 feet when specified.

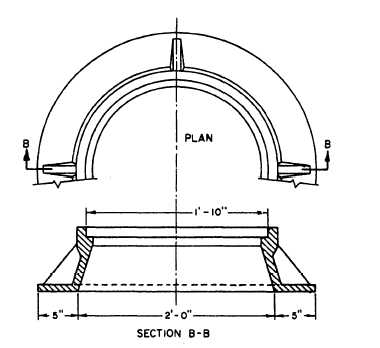

The access opening for a manhole, curb inlet, or

junction box consists of the cover and a supporting

metal frame. A frame for a circular cover is shown in

figure 10-2. Some covers are rectangular. The frame

usually rests on one or more courses of adjusting

blocks so that the rim elevation of the cover can be

varied slightly to fit the surface grade elevation by

varying the vertical dimensions, or the number of

courses, of the adjusting blocks.

A junction box is similar to a manhole but is

installed, of necessity, at a point where two or more

trunk lines converge. The walls of an inlet, manhole,

or junction box maybe constructed of special concrete

masonry units or of cast-in-place concrete. The

bottom consists of a formed slab, sloped in the

Figure 10-2.—Frame for an access opening.

10-5