subangular or subaounded, depending on which shape

predominates.

Laboratory analysis must be performed when

accurate grain size distribution is to be determined.

However, you can approximate the distribution by

visual examination using the following steps:

1. Separate the larger grain particles from the rest

of the soil sample by picking them out one at a time.

2. Examine the remainder of the soil and estimate

the proportion of visible individual particles (larger than

the No. 200 sieve) and the fines.

3. Convert these estimates into percentages by

weight of the total sample. If the fines exceed 50 percent,

the soil is considered fine-grained (M, C, or O); if the

coarse material exceeds 50 percent, the soil is

coarse-grained (G or S).

4. Examine the coarse-grained soil for gradation of

particle sizes from the largest to the smallest. A good

distribution of all sizes without too much or too little of

any one size means the soil is well-graded (W).

Overabundance or lack of any size means the material

is poorly graded (P).

5. Estimate the percentage of the fine-grained

portion of the coarse-grained soil. If nonplastic fines are

less than 5 percent of the total, the soil maybe classified

either as a GW, GP, SW, or SP type, depending on the

other information noted above.

6. If the fine-grained portion (Step 5 above)

exceeds 12 percent, the soil is either silty (M) or clayey

(C) and requires further testing to identify.

7. Fine-grained portions (Step 5 above) between 5-

and 12-percent (nonplastic fines or fines not interfering

with drainage, or 0 to 12 percent plastic fines) total are

border line and require a double symbol (GW-GM or

SW-SM).

8. Fine-grained soils (M, C, or O) from Step 3

above require other tests to distinguish them further.

Grain size distribution of fine portions is normally not

performed in field identification. However, should it

become necessary, you can approximate the grain size

of the fines by shaking them in a jar of water and

allowing the material to settle. The materials settle in

layers of different sizes from which the proportion can

be estimated. It should be kept in mind that gravel and

sand settle into a much denser mass than either clay or

silt.

If you use the characteristics determined up to this

point, it is possible to evaluate the soil as it appeared in

place (undisturbed). Gravels or sands can be described

qualitatively as loose, medium, or dense. Clays maybe

hard, stiff, or soft. The ease or difficulty with which the

sample was removed from the ground is a good

indicator. Soils that have been cultivated or farmed can

be further evaluated as loose and compressible. Highly

organic soils can be spongy and elastic. In addition,

moisture content of the soil influences the in-place

characteristics. This condition should be recognized and

reported with the undisturbed soil properties.

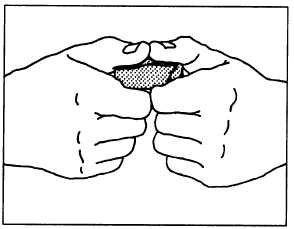

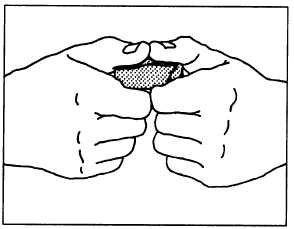

BREAKING OR DRY-STRENGTH

TEST

The breaking test is done only on the material

passing the No. 40 sieve. This test as well as the roll test

and the ribbon test, is used to measure the cohesive and

plastic characteristics of the soil. The test normally is

made on a small pat of soil about 1/2 inch thick and about

1 1/2 inches in diameter. The pat is prepared by molding

a portion of the soil in the wet plastic state into the size

and shape desired and then allowing the pat to dry

completely. Samples may be tested for dry strength in

their natural condition as they are found in the field

However, you should not depend too much on such tests

because of the variations that exist in the drying

environment under field conditions. You may

approximate the dry strength by such a test however,

and verify it later by a carefully prepared sample.

After the prepared sample is thoroughly dry, attempt

to break it using the thumbs and forefingers of both

hands (fig. 16-5). If you are able to break it, then try to

powder it by rubbing it with the thumb and fingers of

one hand.

Figure 16-5.-Breaking or dry-strength test.

16-17